Selling Assets While Racing for a Banking License — What Is PayPal So Anxious About?

PayPal Is Launching a Bank

On December 15, the global payments giant with 430 million active users officially filed an application with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the Utah Department of Financial Institutions to establish an industrial bank (ILC) named “PayPal Bank.”

Yet, just three months earlier on September 24, PayPal announced a major deal: it bundled and sold $7 billion worth of “buy now, pay later” loan assets to asset management firm Blue Owl.

During the earnings call, CFO Jamie Miller assured Wall Street that PayPal’s strategy was to “maintain a light balance sheet,” focusing on freeing up capital and boosting efficiency.

These moves seem contradictory—on one hand, PayPal pursues a lighter asset structure, while on the other, it seeks a banking license. Banking is one of the most capital-intensive businesses in the world, requiring hefty capital reserves, intense regulatory scrutiny, and direct exposure to deposit and lending risks.

Behind this apparent contradiction lies a strategic compromise driven by urgent necessity. This is not a routine business expansion; it’s a calculated maneuver to secure a foothold amid tightening regulatory boundaries.

PayPal’s official rationale is “to provide lower-cost loan capital to small businesses,” but this explanation doesn’t withstand scrutiny.

Since 2013, PayPal has issued more than $30 billion in loans to 420,000 small businesses worldwide—all without a banking license. If PayPal’s lending business has thrived for 12 years without a charter, why apply for one now?

To answer that, we first need to ask: who actually issued those $30 billion in loans?

PayPal: The “Sublessor” of Lending

PayPal’s press releases highlight impressive lending figures, but the core fact is often overlooked: none of those $30 billion in loans were actually issued by PayPal. The real lender is WebBank, based in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Most people have never heard of WebBank. It’s an enigmatic institution—no consumer branches, no advertising, and a minimal website presence. Yet in the shadowy corners of US fintech, WebBank is a critical player.

WebBank is the lender behind PayPal’s Working Capital and Business Loan products, Affirm’s installment plans, and Upgrade’s personal loans.

This structure is known as “Banking as a Service (BaaS).” PayPal handles customer acquisition, risk management, and user experience; WebBank’s sole role is to provide the banking license.

Think of PayPal as a “sublessor”—the actual title deed belongs to WebBank.

For technology companies like PayPal, this arrangement was ideal. Securing a banking license is slow, complex, and expensive, and applying for lending licenses in all 50 states is a bureaucratic nightmare. Leasing WebBank’s charter is a VIP fast track.

But the biggest risk in “renting” is that the landlord can end the lease, sell, or even demolish the property at any time.

In April 2024, a black swan event shook US fintech. Synapse, a BaaS intermediary, abruptly filed for bankruptcy, freezing $265 million in funds for over 100,000 users and leaving $96 million unaccounted for—some lost their life savings.

This disaster exposed major vulnerabilities in the “sublessor” model. If any link fails, years of user trust can evaporate overnight. Regulators responded with strict BaaS scrutiny, and several banks faced fines and business restrictions over compliance failures.

For PayPal, even though its partner is WebBank (not Synapse), the risk is the same. If WebBank falters, PayPal’s lending business grinds to a halt. If WebBank changes its terms, PayPal has no leverage. If regulators force WebBank to tighten partnerships, PayPal is powerless. That’s the dilemma: you run the business, but your lifeline is in someone else’s hands.

There’s another, more tempting driver for PayPal’s leadership: windfall profits in a high-rate environment.

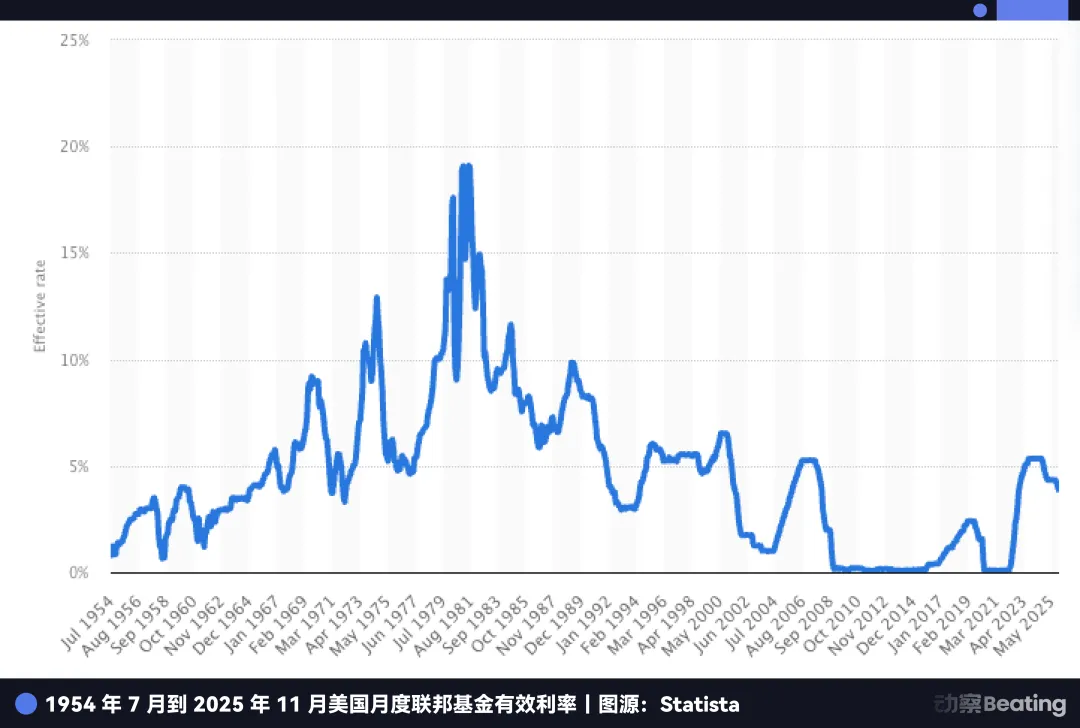

For the past decade of zero interest rates, banking wasn’t attractive—there was little spread between deposits and loans. Today, the landscape has changed.

Even as the Fed begins to cut rates, the US benchmark rate remains near a historic high of 4.5%. Deposits are now a gold mine.

PayPal’s dilemma: it controls a massive pool of funds from 430 million active users, but those funds sit in PayPal accounts and must be deposited with partner banks.

The partner banks use this low-cost capital to buy US Treasuries yielding 5% or issue higher-rate loans, reaping huge profits. PayPal gets only a small cut.

If PayPal secures its own banking license, it can turn idle user funds into low-cost deposits, buy Treasuries, issue loans, and keep all the spread profits in-house. In this high-rate window, that means billions in additional profit.

But if the goal was simply to cut ties with WebBank, PayPal could have acted sooner. Why wait until 2025?

The answer lies in a deeper, more urgent anxiety: stablecoins.

PayPal: Still a “Sublessor” in Stablecoins

If being a “sublessor” in lending meant less profit and more risk for PayPal, in stablecoins, this dependency is an existential threat.

In 2025, PayPal’s stablecoin PYUSD exploded, tripling its market cap to $3.8 billion in three months. Even YouTube announced PYUSD integration in December.

Yet behind the headlines, there’s a fact PayPal doesn’t advertise: PYUSD isn’t issued by PayPal, but by Paxos, a New York-based company, under a partnership.

It’s another “white-label” arrangement—PayPal licenses its brand, just as Nike outsources manufacturing but keeps the logo.

Previously, this division of labor made sense: PayPal owned the product and users, Paxos handled compliance and issuance, and both parties benefited.

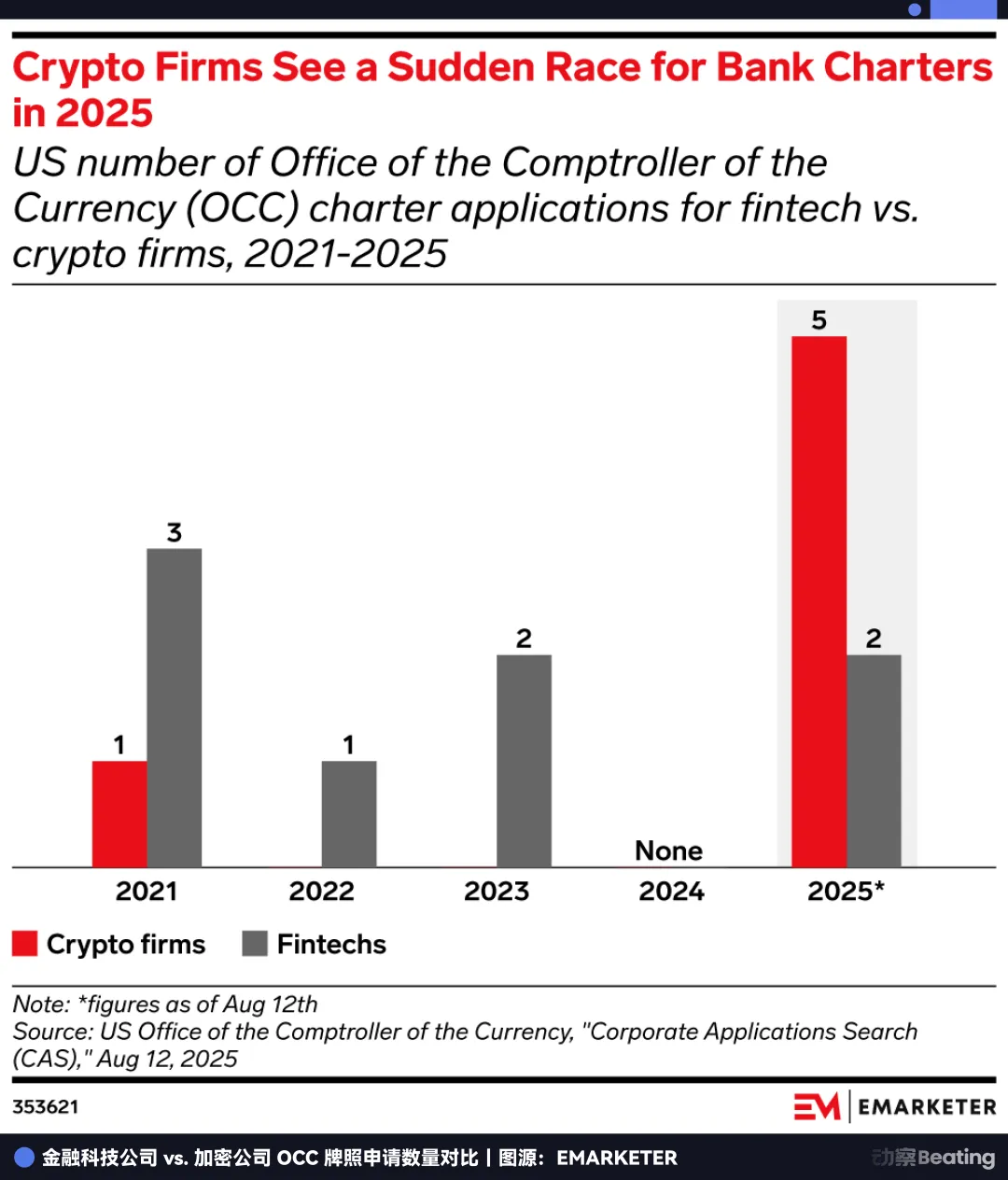

But on December 12, 2025, the OCC gave “conditional approval” for national trust bank licenses to several institutions, including Paxos.

This isn’t a full commercial bank license (with deposit-taking or FDIC insurance), but it means Paxos is moving into the spotlight as a licensed issuer.

Factor in the “GENIUS Act” and PayPal’s urgency is clear. The act allows regulated banks to issue payment stablecoins via subsidiaries, concentrating issuance rights and profits among licensed entities.

Previously, PayPal could treat stablecoins as an outsourced module. Now, as the partner gains stronger regulatory status, it’s no longer just a supplier—it could become a competitor.

PayPal’s predicament: it controls neither the issuance infrastructure nor regulatory status.

The rise of USDC and OCC’s trust charter approvals send a clear signal: in the stablecoin race, victory goes to whoever controls issuance, custody, settlement, and compliance.

So, PayPal isn’t just seeking to become a bank—it’s securing a ticket to the future. Without it, PayPal remains on the sidelines.

More urgently, stablecoins threaten PayPal’s core business model.

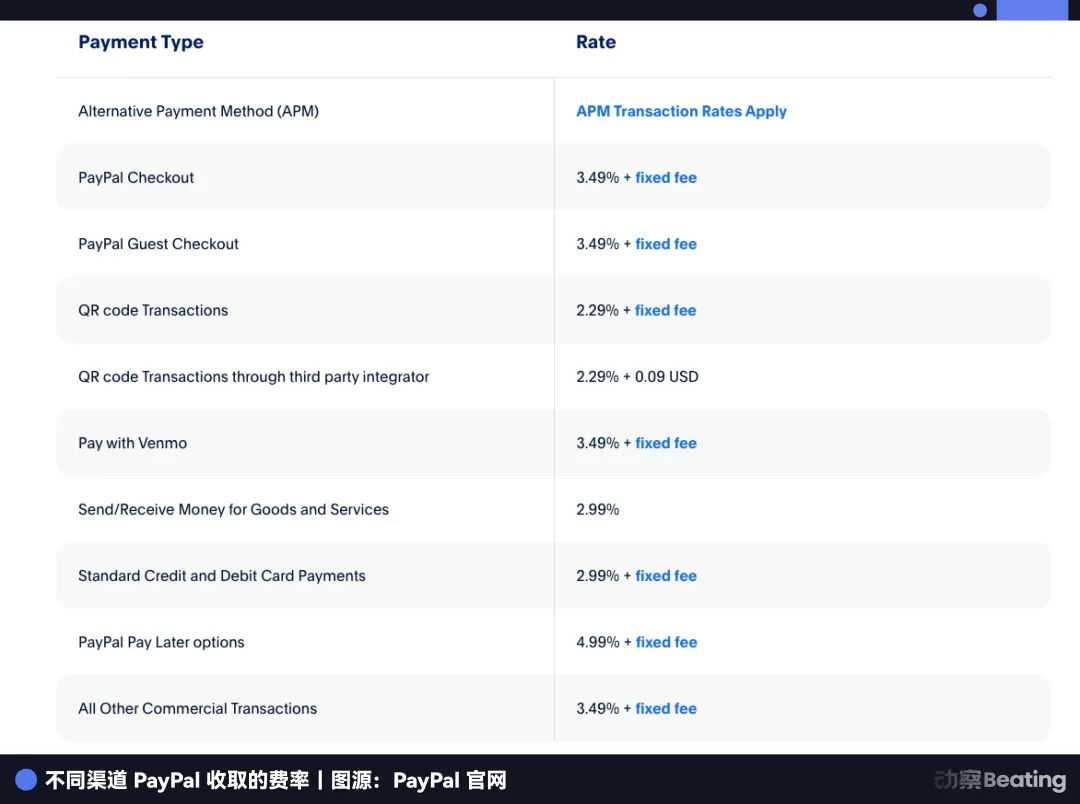

PayPal’s most profitable segment is e-commerce payments, earning 2.29–3.49% per transaction. Stablecoins operate differently—near-zero transaction fees, with profits coming from interest on user funds held in Treasuries.

As Amazon accepts USDC and Shopify enables stablecoin payments, merchants face a simple choice: why pay PayPal a 2.5% fee when stablecoins cost almost nothing?

Currently, e-commerce payments generate over half of PayPal’s revenue. Market share has dropped from 54.8% to 40% in recent years. Without control over stablecoins, PayPal’s moat disappears.

PayPal’s situation now mirrors Apple’s experience with Apple Pay Later. In 2024, Apple, lacking a banking license and constrained by Goldman Sachs, shut down the service and refocused on hardware. Apple could retreat—hardware is core, finance is a bonus.

PayPal has no such fallback.

It has no phones, no OS, no hardware ecosystem. Finance is everything—its only revenue stream. Apple’s retreat is strategic; for PayPal, retreat means extinction.

So PayPal must push forward. It must secure a banking license and bring stablecoin issuance, control, and profits in-house.

But launching a bank in the US is daunting—especially for a tech company with $7 billion in loan assets. Regulatory approval thresholds are sky-high.

To secure its ticket to the future, PayPal engineered a sophisticated capital maneuver.

PayPal’s Strategic Transformation

Let’s revisit the contradiction from the start.

On September 24, PayPal sold $7 billion in “buy now, pay later” loans to Blue Owl, with the CFO publicly declaring a “lighter” balance sheet. Wall Street analysts saw it as a move to improve financials and cash flow.

But viewed alongside the bank license application three months later, it’s clear this was a coordinated strategy, not a contradiction.

Without offloading those $7 billion in receivables, PayPal’s bank charter application would almost certainly fail.

Why? US regulators require a stringent “health check” for bank applicants. The FDIC uses the capital adequacy ratio as a key metric.

The logic: the more high-risk assets (like loans) on your balance sheet, the more capital you must hold as a buffer.

If PayPal applied for a license carrying $7 billion in loans, regulators would see a heavy risk burden: “With all these risky assets, can you cover potential losses?” This could require massive capital reserves and likely rejection.

So PayPal had to slim down before the review.

The Blue Owl deal is a forward flow agreement—a smart design. PayPal offloads all new loan receivables and default risk for the next two years to Blue Owl, but cleverly keeps underwriting rights and customer relationships—the “money printer” remains in-house.

To users, nothing changes—they still borrow from and repay via PayPal’s app. But for the FDIC, PayPal’s balance sheet is instantly cleaner and leaner.

Through this transformation, PayPal shifts from a lender bearing default risk to a fee-based intermediary.

Asset shuffling to pass regulatory scrutiny isn’t new on Wall Street, but rarely is it done so decisively or at this scale. It demonstrates PayPal’s resolve—even if it means giving up lucrative interest income, it’s worth it for a long-term future.

And the window for this bold move is closing quickly. PayPal’s urgency comes from the fact that the “back door” it’s targeting is being shut—possibly for good—by regulators.

The Closing Back Door

PayPal is applying for an Industrial Loan Company (ILC) charter—a structure few outside finance know, but one of the most coveted in US regulatory circles.

Look at the roster of ILC holders: BMW, Toyota, Harley-Davidson, Target…

Why do automakers and retailers want to run banks?

The ILC is a unique regulatory loophole in US law allowing non-financial giants to operate banks.

The loophole comes from the 1987 Competitive Equality Banking Act (CEBA). Despite its “equality” name, it grants ILC parent companies an exceptional privilege: exemption from registering as a bank holding company.

With a regular bank license, your parent company is subject to Federal Reserve oversight. With an ILC, the parent (e.g., PayPal) bypasses the Fed, answering only to the FDIC and Utah regulators.

This means you get national privileges—deposit-taking, access to federal payment rails—while avoiding Fed interference in business strategy.

This is regulatory arbitrage, and it also allows for “mixed business operations.” That’s how BMW and Harley-Davidson vertically integrate their value chains.

BMW Bank doesn’t need branches—its services are embedded in the car-buying process. When you buy a BMW, the sales system connects you to BMW Bank’s loan services.

BMW profits from both car sales and auto loans. Harley-Davidson goes further—its bank can lend to loyal riders traditional banks reject, because Harley knows their default rates are low.

This is PayPal’s ultimate goal: payments on one hand, banking on the other, stablecoins in between, with no outside interference.

If the loophole is so valuable, why haven’t Walmart or Amazon applied to start their own banks?

Because traditional banks fiercely oppose this back door.

Bankers see commercial giants with massive user data as existential threats. In 2005, Walmart’s ILC application sparked a banking industry revolt. Bank associations lobbied Congress, arguing that if Walmart Bank used shopping data to offer cheap loans to its customers, community banks would be wiped out.

Under intense pressure, Walmart withdrew its application in 2007. Regulators then froze ILC approvals—none were granted from 2006 to 2019. Only in 2020 did Square (now Block) break the deadlock.

Now, just as the back door reopened, it’s again at risk of permanent closure.

In July 2025, the FDIC issued a request for comment on the ILC framework—a clear sign of a regulatory crackdown. Related legislation in Congress is ongoing.

This triggered a rush for licenses. In 2025, US bank charter applications hit a record 20; the OCC alone received 14 applications, equal to the total from the previous four years.

Everyone knows this is the last chance before the door closes. PayPal is racing the regulators—if it doesn’t get in before the loophole is sealed, it may never have another shot.

A Final Breakout

The license PayPal is fighting for is essentially an “option.”

Its current value is clear: autonomous lending and capturing interest margins in a high-rate environment. Its future value lies in enabling PayPal to enter currently restricted, high-potential markets.

Wall Street’s most lucrative business isn’t payments—it’s asset management.

Without a banking license, PayPal is just a conduit for user funds. With an ILC charter, it becomes a legal custodian.

This means PayPal could legally hold Bitcoin, Ethereum, and future RWA assets for 430 million users. In the future, under the “GENIUS Act,” banks may be the only legal gateway to DeFi protocols.

Imagine a future PayPal app with a “high-yield investment” button, connecting to DeFi protocols like Aave or Compound, with compliance handled by PayPal Bank. This would break down the wall between Web2 payments and Web3 finance.

At that point, PayPal isn’t just competing with Stripe on fees—it’s building the financial operating system for the crypto era, evolving from transaction processor to asset manager. Transactions are finite; asset management is an infinite game.

This is why PayPal is making a decisive push at the end of 2025.

PayPal knows it’s caught in a historic squeeze. On one side, stablecoins threaten to erase payment profits; on the other, the ILC regulatory loophole is about to be welded shut.

To break through, PayPal had to sell $7 billion in assets in September—a radical move to secure its survival ticket.

Viewed over 27 years, this is a story of destiny coming full circle.

In 1998, when Peter Thiel and Elon Musk founded PayPal’s predecessor, their mission was to “challenge banks” and disrupt outdated, inefficient financial institutions with digital money.

Twenty-seven years later, the former “dragon slayer” is doing everything possible to “become a bank.”

There are no fairy tales in business—only survival. On the eve of a crypto-driven financial reordering, remaining an “ex-giant” outside the system leads only to extinction. Only by securing that regulatory status—even through a “back door”—can you survive into the next era.

This is a do-or-die breakout that must be completed before the window closes.

If PayPal succeeds, it becomes the JPMorgan Chase of Web3. If it fails, it’s just a relic of the last Internet era.

Time is running out for PayPal.

Statement:

- This article is reprinted from [动察 Beatiing], copyright belongs to the original author [Sleepy.txt]. If you have any objections to this reprint, please contact the Gate Learn team, and we will process it promptly according to our procedures.

- Disclaimer: The views and opinions in this article are solely those of the author and do not constitute investment advice.

- Other language versions of this article are translated by the Gate Learn team. Unless Gate is cited, do not copy, distribute, or plagiarize the translated article.

Related Articles

The Future of Cross-Chain Bridges: Full-Chain Interoperability Becomes Inevitable, Liquidity Bridges Will Decline

Solana Need L2s And Appchains?

Sui: How are users leveraging its speed, security, & scalability?

Navigating the Zero Knowledge Landscape

What is Tronscan and How Can You Use it in 2025?